Walter Rodney showed how colonialism built the wealth of the West at Africa’s expense – and left behind lessons we need today

In 1885, brothers William and James Lever from Liverpool started making soap. Within two decades, they were selling 60,000 tons of Lifebuoy and Lux soap in Britain. Their formula relied on palm and groundnut oils; to secure these at the source, in 1902 the Levers established oil palm plantations (67,800 km2 of them – just under the size of Ireland) in the Congo, then the personal fiefdom of the genocidal King Leopold II of Belgium. By 1929, the Levers had incorporated their competitors into a single monopoly: Unilever. These lands remain oil palm monocultures today. Congolese farmers now work on what is their ancestral land for about $20 a month. Unilever’s global revenue in 2019 was €52bn.

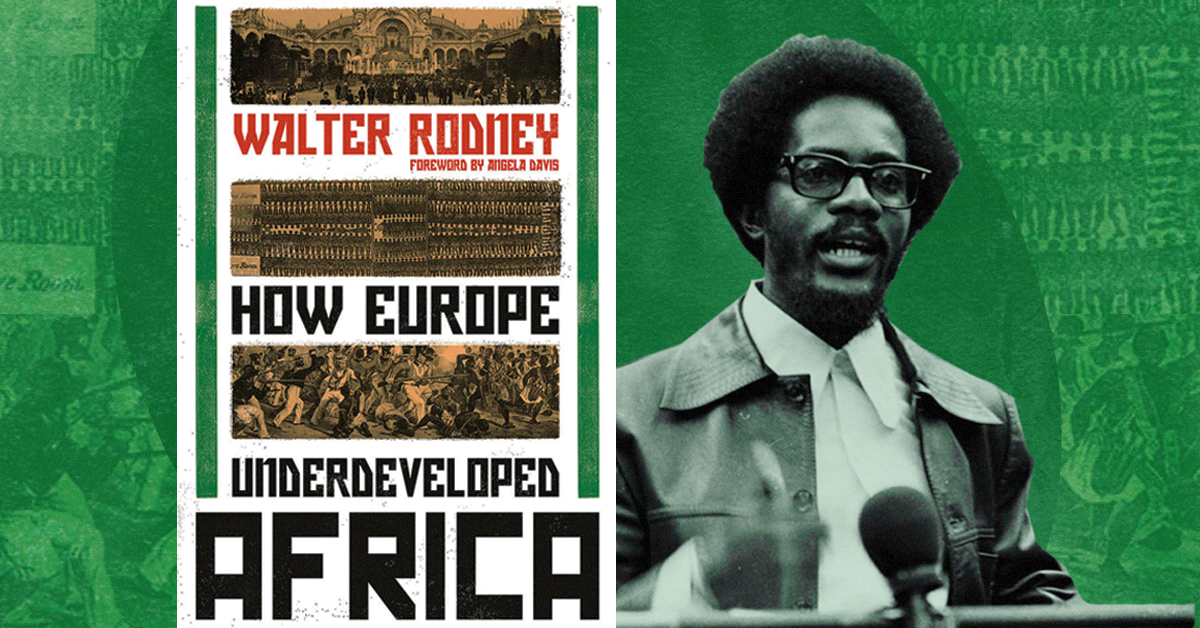

A groundbreaking book detailed countless examples like this. “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa”, published in 1972, is a magisterial survey of how European colonialism completely changed Africa’s own historical trajectory. It charts how, far from “modernising” the continent, colonialism implemented an extractive and export-based economy that to this day ensures Africa’s under-development. Walter Rodney, its author, was a historian as well as a grassroots labour activist. Born in Georgetown, Guyana in 1942, he won a scholarship to the University of the West Indies (UWI) in Jamaica in 1960, where he studied history. Rodney then attended SOAS, University of London, for a PhD in African history between 1963 and 1966.

While there, Rodney stood out. He challenged many points of consensus in the academy. Where historians argued that existing systems of servitude in Africa had helped enable the European slave trade, Rodney showed through evidence that Europe also introduced slavery to parts of Africa where historically there was none. Where economists focused on politics to understand Africa’s pre-colonial history, Rodney looked for answers in the way African societies organised their means of production. “His research raised a whole set of fresh questions… he helped to open up a new dimension,” wrote Richard Gray, a Professor of African History, in Rodney’s obituary.

There was no ivory tower for Rodney: his scholarship was valid only if he could explain it to ordinary people, and use it to hear and address their problems. Returning to Jamaica in 1968 to teach at his alma mater UWI, he gathered students, working-class Jamaicans and Rastafarians in open lectures and forums of discussion called “groundings”. He facilitated conversations about the social and political problems affecting their everyday lives; they taught him Rastafari spirituality and wisdom. So evidently dangerous was this exchange to the Jamaican government that Rodney was banned from the country in October 1968. This not only sparked revolt in Kingston, it didn’t silence him: the lectures and discussions at UWI were published in 1969 as The Groundings With My Brothers. If anything, Rodney’s experience in Jamaica convinced him that “to be a ‘revolutionary intellectual’ means nothing if there is no point of reference to the struggle.”

He went to Tanzania, then helmed by the socialist president Julius Nyerere, to teach from 1969 to 1974. There, Rodney started looking at detailed statistics, economic indicators, and historical records to ask why Africa, the richest continent in terms of natural resources, had so much poverty. The result – How Europe Underdeveloped Africa – uncovered how (during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in particular) Africa was bled dry to fuel the agricultural, industrial, economic, technological development of Europe. Palm oil, groundnuts, rubber. Gold, iron, manganese. Cobalt, copper – and later, uranium. The mining that went on in Africa “left holes in the ground, the mass agriculture left African soils impoverished; but in Europe, these agricultural and mineral imports built a massive industrial complex,” Rodney wrote (1972, 214). The extraction of African labor and resources enriched the West while degrading the continent’s capacity for self-determined development.

Today’s environmental catastrophe is an extension of this logic: the Global South bears the brunt of climate change’s effects despite contributing least to the crisis (Nature 2025). Just as Europe’s unchecked extraction of Africa’s natural resources and human labour deliberately underdeveloped the continent in the nineteenth century, we are now seeing another violent scramble for raw materials vital to electrification. In Nigeria, the lithium boom has led to the proliferation of illegal mines where children as young as six work under hazardous conditions for meagre wages. These operations often involve dangerous practices, such as using rudimentary tools and exposure to toxic dust, with little to no regulatory oversight (Adebayo 2024). In Chile’s Salar de Atacama, lithium extraction consumes a substantial portion of the region’s freshwater resources, exacerbating drought conditions and impacting Indigenous communities (Greenfield 2022). The mining operations have led to protests and demands for greater environmental protections and respect for Indigenous rights, as the extraction processes threaten traditional ways of life and local ecosystems. Rodney’s historical method – dialectical, structural, and materially grounded – unmasks the long arc of imperialist exploitation that creates these contemporary challenges.

Rodney argued that while European capitalism allowed for some meagre share of this wealth to trickle down to its own working classes, it did not create African capitalists in Africa. When Africans did try industrialising for themselves, it was blocked by gun and decree. For instance, when West Africans tried in 1927 to mill the groundnut oil they grew for export, they were restricted by the French colonial government. Nothing more was wanted from Africans but to grow, pick, and dig. Refining and manufacturing their raw resources into their own products – the industrial steps that create jobs, know-how, and profit – were systematically denied them. Rodney points to the many irrational contradictions that arose as a result of this non-industrialisation policy: Sudanese and Ugandans grew cotton but imported manufactured cotton goods, Côte D’Ivoire grew cacao but imported chocolate. It was a recipe, in short, for guaranteeing a future of dependency. This systemic denial of technological sovereignty finds echoes in today’s digital divides and techno-authoritarianism, where innovation benefits capital-rich nations while disenfranchising the majority world (Campbell 1981, 54). Despite Africa’s aspirations to participate in cutting-edge technologies, infrastructural challenges persist. With only 5% of potential AI contributors having access to necessary computational resources (Ekonde 2025), the continent risks repeating historical patterns of underdevelopment, where technological progress is dictated by external powers.

Rodney’s work continues to strike a chord in many circles, from labour movements in the U.S. to anti-colonial movements in the Caribbean. This is because even though it was a history book, it also read like a guide to how this exploitation continues in the present. A lot of people saw how their own postcolonial nation-states – those results of the hard-won battle for independence from colonialism – could be complicit in the continuation of the same old economy. The independences that had swept across Africa in the 1960s and ‘70s, it turned out, had not meant the freedom to forge a new path. What was once colonial extraction was continuing as Western private enterprise, aided by complicit African national governments.

Rodney’s challenging this state of affairs – one often called neo-colonialism – would spell his end. He left Tanzania for his home country Guyana in 1974, but life wasn’t easy – a professorship offered to him was retracted, and his wife Patricia Rodney was blocked from her nursing career. He co-founded a multi-racial socialist party, the Working People’s Alliance, where he and other progressive-minded Guyanese worked towards the empowerment of workers and farmers. He found some opportunities to lecture and teach through African American colleagues, who urged him to join them in the U.S. for safety. But for Rodney, the privilege of having the ready means of escape meant the responsibility to remain with those he worked beside. The Guyanese government increased its repression and intimidation of Rodney and other leaders of the WPA throughout 1979; on 13 June 1980, Rodney was assassinated in Georgetown by car bomb.

His example of pedagogy as dialogue and political practice lives on. It should guide our approach to confronting authoritarianism, anti-intellectualism, and the eroding of institutional trust today. Rodney grounded his intellectual work among the disenfranchised, listening to Rastafari brethren, peasants, and workers (Hudson 2023, 98; Campbell 1981, 55). He embodied a praxis that defied both academic elitism and state repression. In our era, marked by a billionaire-owned media that peddles xenophobia, individualism, and polarisation, Rodney’s emphasis on collective empowerment and grassroots solidarity reminds us that real change cannot come from technocratic fixes or personal escapism. He urged instead a sober, methodical analysis of the present, rooted in the needs and knowledges of the oppressed (Hudson 2023, 101), who were co-creators of their own liberation.

This urging has been heard and understood in the contemporary Caribbean; Rodney’s ideas continue to surface in both institutional settings and grassroots movements. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa remains a foundational text in regional university curricula, especially at the University of the West Indies, where scholars continue to frame it as a political tool as much as an academic one. During the 50th anniversary commemoration of the book, historian Horace Campbell highlighted Rodney’s enduring relevance by linking his critique of neocolonial elites to present-day struggles for democratic accountability and economic justice in places like Guyana and Jamaica (Trotz and Westmaas 2023, 178–79). Rodney’s influence is evident too in Caribbean culture – the 2018 reggae song “Flames” by Protoje featuring Chronixx, for example, mentions his exile. Recent debates over educational reform echo Rodney’s critiques of colonial schooling as a tool of subordination; Zuleica Romay Guerra (2022) argues his views on popular education and cultural decolonisation resonate with ongoing Cuban efforts to reinterpret African and diasporic history outside of Eurocentric frameworks. Rupert Lewis (1998) has situated Rodney’s role in shaping a Black radical tradition that continues to challenge post-independence elites and their complicity in reproducing structural inequalities. These interventions ensure that Rodney’s voice remains active – not as historical relic, but as a guide for confronting the enduring legacies of empire.

His clear-sighted work gives us the much-needed facts. Those facts are the historical threads that connect the beneficiaries of this world to its dispossessed. It is a fortified bind – upheld today by a mixture of state, corporate, military and criminal powers – but for Rodney, that made it all the more necessary to sever. To meet our moment, we must not only study his analyses, but emulate his method: engage history as a tool for diagnosis, see the common threads between our struggles, and co-create political consciousness from below.

________________

Dr. Sarah Jilani is a Lecturer in English at City, University of London who teaches postcolonial literatures and world cinema. As is a freelance writer on books, film and contemporary art, her articles have appeared in ArtReview, The Times Literary Supplement, The Guardian and The Economist, among others. She is the author of Subjectivity and Decolonisation in the Post-Independence Novel and Film (Edinburgh University Press, 2024), and regularly appears on BBC Radio 4 as a 2021 AHRC/BBC New Generation Thinker.

This essay is a republication from The Times Literary Supplement, originally published July 2020. It is reproduced here with permission from Sarah Jilani.